Making Bets

In this post I simulate various betting strategies using the logistic regression and multi-layer perceptron models from my previous post, Predicting NBA Games with Machine Learning.

In Predicting NBA Games with Machine Learning, I used nearest neighbors, support vector machine, logistic regression, and multi-layer perceptron models to predict the winners of NBA games using player and team statistics. The logistic regression and multi-layer perceptron models output for each game a predicted probability of the home team winning, which is then rounded to $0$ or $1$ to make the prediction. Nearest neighbors and the support vector machine on the other hand, do not output probabilities, they just output a binary $0$ or $1$. This difference is why logistic regression and the multilayer perceptron are used in this post to devise betting strategies. The finer information of a predicted probability allows for comparison with betting odds to make interesting betting strategies.

In [HSZ], Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný devise a successful betting strategy using predictions from a multilayer perceptron model with a convolutional layer and a nonstandard loss function. The betting strategy they use is based on concepts from economics. Their work inspired my work here, and their methods will be explained and compared to mine.

The code for this project that is references throughout is available at my github, here.

Set Up

In this section, the theoretical framework for the problem of betting on games is stated. For a given game, say Team $A$ versus Team $B$, let $p$ denote the probability that Team $A$ will win. Assume there is a predictive model that produces for each game a probability for each team winning. Let $\hat{p}_m$ be the probability Team $A$ wins given by the model. Let $\hat{p}_o$ be the probability Team $A$ wins given by the betting odds.

Let $b$ be the amount a bettor bets on the game. If the bettor wins the bet, (s)he wins $b\cdot\frac{1}{\widehat{p}_o}-b$ dollars (this means (s)he has $b\cdot\frac{1}{\widehat{p}_o}-b$ more dollars than (s)he had before making the bet, see this post for where the formula comes from). If (s)he loses the bet, (s)he wins $-b$ dollars (this means she has $b$ less dollars than (s)he had before making the bet). Let the winnings of the bettor when betting $b$ dollars be denoted by the random variable $W$. Then the expected value of $W$ determined by the model is

\[\begin{equation}\hat{E}(W) = \left(\frac{b}{\hat{p}_o} - b\right)\hat{p}_m - b(1 - \hat{p}_m) = b\left(\frac{\hat{p}_m - \hat{p}_o}{\hat{p}_o}\right).\end{equation}\]This should be thought of as a predicted expected value. It is an estimate of the actual expected value, which is

\[\begin{equation}E(W) = \left(\frac{b}{\hat{p}_o} - b\right)p - b(1 - p) = b\left(\frac{p - \hat{p}_o}{\hat{p}_o}\right).\end{equation}\]The difference between $E(W)$ and $\hat{E}(W)$ is the actual probability $p$ versus its estimate $\hat{p}_m$. The actual probability $p$ is unknowable. In equation $(2)$, one sees the betting margin. The betting margin is the difference between $\hat{p}_o$ and $p$. If $\hat{p}_o > p$, which is always the case with real betting odds, then the expected winnings, $E(W)$, is negative.

Intuitively, the larger $\hat{p}_m - \hat{p}_0$ is, the more the bettor should bet on the game. This is reflected in $\hat{E}(W)$. The question to answer is not how much to bet on one game though. It is the following: Given a series of rounds, where each round consists of a bunch of games, what is the best strategy for betting on all the games in each round?

This question is formalized as follows: Say there are $n$ games one round. Assume the $i$th game, $1\leq i\leq n$, is between Team $A_i$ and Team $B_i$ with Team $A_i$ having real probability $p_i$ of winning, model predicted probability $\hat{p}_{m,i}$ of winning, and betting odds probability $\hat{p}_{o,i}$ of winning. For $1\leq i\leq n$, let $\hat{p}_{o,n + i}$ be the betting odds probability of Team $B_i$ winning. The real probability and model predicted probability of Team $B_i$ winning are $1 - p_i$ and $1 - \hat{p}_{m,i}$ respectively. For $1\leq i\leq n$, let $b_i$ and $b_{n + i}$ be the amounts bet on Team $A_i$ and Team $B_i$ to win respectively, and let $W_i$ and $W_{n + i}$ be the winnings from the bets on Team $A_i$ and Team $B_i$ respectively. Let $W$ be the sum of the $W_i$, so $W$ is the overall winnings of the bets on the $n$ games.

The model’s expected winnings of the bets on these $n$ games is

\[\begin{equation} \hat{E}(W) = \sum_{i = 1}^{2n} \hat{E}(W_i) = \sum_{i = 1}^n b_i\left(\frac{\hat{p}_{m,i} - \hat{p}_{o,i}}{\hat{p}_{o,i}}\right) + b_{n + i}\left(\frac{1 - \hat{p}_{m,i} - \hat{p}_{o, n+i}}{\hat{p}_{o, n+i}}\right).\end{equation}\]As noted in [HSZ], to maximize $\hat{E}(W)$, the bettor would bet all his/her money on the game and team with the highest expected winnings and no money on all the other games. This is not the best in practice when betting multiple rounds because one incorrect bet bankrupts the bettor. One wants to determine how the bettor should spread out his/her money over all the games to make the most money when betting multiple rounds.

There are two important aspects to answering this question in such a way as to have the bettor make money: have an accurate predictive model that is not correlated with the betting odds predictions, and spreading out the money on bets well.

Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný

The two aspects of [HSZ] I focus on are how they decorrelate their predictive model from the betting odds, and how they choose to make the bets $b_i$ in a given round.

In order for a bettor to win money betting over time, it is important to not just win a large percentage of bets but also to bet consistently on the underdog with respect to the betting odds. This means that the more your predictive model is correlated with the betting odds, the more money you will lose betting. In their multilayer perceptron models, [HSZ] use a loss function that decorrelates the predictions from the betting odds predictions. The loss function is the following: Let $X$ be a training dataset with $N$ games. For the $i$th game in $X$, let $y_i$ be the result of whether or not the home team won, $\hat{p}_{o, i}$ the betting odds probability of the home team winning, and $\hat{p}_i$ the machine learning algorithm’s prediction of the probability of the home team winning. Then for a constant, $c$, $0\leq c \leq 1$, [HSZ] define the loss function

\[\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i = 1}^N(\hat{p}_i - y_i)^2 - c(\hat{p}_i - \hat{p}_{o,i})^2.\]The $(\hat{p}_i - y_i)^2$ term is a normal loss function term. The $c(\hat{p}_i - \hat{p}_{o,i})^2$ is a new term that decorrelates the model from the betting odds predictions. It measures the difference between the model’s predicted probability and the betting odds’ predicted probability. The larger $c(\hat{p}_i - \hat{p}_{o,i})^2$ is, the smaller the loss is. Therefore this loss function favors models whose predictions differ from the betting odds predictions. Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný experiment with various $c$’s, finding that $c$ in the range $0.4\leq C\leq 0.8$ works best.

With the prediction model of a multilayer perceptron with a convolutional layer trained with the above loss function, Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný devise a successful betting strategy by choosing the bets $b_i$ in a given round of games cleverly. Their strategy is to solve the multi-objective optimization problem of maximizing the expectation of winnings, $\hat{E}(W)$, while minimizing the variance of winnings, $\widehat{Var}(W)$.

If we assume for each $i$, $1\leq i\leq n$ that the bettor does not bet on Team $A_i$ and Team $B_i$, and we assume that no team appears twice in a round, then all the games are independent. Then one may calculate $\widehat{Var}(W)$ as

\[\widehat{Var}(W) = \sum_{i = 1}^{2n} \widehat{Var}(W_i).\]For the $i$th game,

\[\hat{E}(W_i^2) = b_i^2\left(\frac{1}{\hat{p}_{o,i}} - 1\right)^2\hat{p}_{m, i} + b_i^2(1 - \hat{p}_{m, i}),\]so (after some rearranging and simplification),

\[\widehat{Var}(W_i) = \frac{b_i^2 \hat{p}_{m,i}}{\hat{p}_{o,i}^2}(1 - \hat{p}_{m,i}).\]Then, using that $\hat{p}_{m,n + i} = 1 - \hat{p}_{m,i}$,

\[\begin{equation}\widehat{Var}(W) = \sum_{i = 1}^n (1 - \hat{p}_{m,i})\hat{p}_{m, i}\left(\frac{b_i^2}{\hat{p}_{o,i}^2} + \frac{b_{n + i}^2}{\hat{p}_{o,n+i}^2}\right),\end{equation}\]where for each term in $(4)$, one of $b_i$ and $b_{n + i}$ is $0$.

Precisely now, the strategy in [HSZ] is to choose the $b_i$ to simultaneously maximize $(3)$ and minimize $(4).$ There is no unique choice of the $b_i$ that does this. There is a set of choices for the $b_i$ that ranges from maximizing $\hat{E}(W)$ and minimizing $\widehat{Var}(W)$. This set is called the Pareto front, a concept that comes from economics. To decide which choice from the Pareto front to use, they choose the unique one that maximizes the ratio

\[\begin{equation}\frac{\hat{E}{W}}{\hat{\sigma}_W},\end{equation}\]where $\hat{\sigma}_W = \sqrt{\widehat{Var}(W)}$ is the predicted standard deviation. Equation $(5)$ is a special case of a ratio called the Sharpe ratio, which is a ratio that determines an optimization choice in the Pareto front.

Using these two techniques, Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný produce a betting strategy that consistently wins money. Motivated by these ideas, I created a simplified betting strategy. In the future I would like to more closely recreate the results in [HSZ].

Betting Odds Predictions

Before getting to betting strategies and simulated betting, I give some more information about the betting odds data and betting odds predictions. See also the betting odds data section from Predicting NBA Games with Machine Learning for further information on the betting odds data.

There are two ways to use betting odds to make a prediction for which team will win: the spread and the money lines (see How Betting Odds Work for an explanation of how betting odds work in general). In either case, it is possible that the betting odds for a game predict a tie, and so do not actually predict a winner. This happens if the spread is 0 or if both the money lines are the same (say for example both are -110). It is also possible that the spread and money lines predict different winners. In the betting odds data, this happened in total, less that 1% of the time. In the following table, the number of games where the money lines and spread odds predicted different winners as well as when each predicted a tie is recorded. The script that produces these numbers is compare_ml_and_spread.py.

| Season | Different Predictions | Money Line Ties | Spread Ties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007-08 | 8 | 21 | 24 |

| 2008-09 | 9 | 13 | 15 |

| 2009-10 | 18 | 3 | 14 |

| 2010-11 | 27 | 5 | 23 |

| 2011-12 | 12 | 2 | 10 |

| 2012-13 | 21 | 9 | 9 |

| 2013-14 | 15 | 11 | 18 |

| 2014-15 | 15 | 3 | 13 |

| 2015-16 | 5 | 14 | 15 |

| 2016-17 | 8 | 18 | 26 |

| 2017-18 | 1 | 12 | 12 |

| 2018-19 | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| 2019-20 | 3 | 13 | 14 |

| Total | 142 | 142 | 211 |

For this project, the money line predictions are used because they produce the predicted probabilities of each team winning. The following table records the percentage of games the money lines predicted correctly for each season in the dataset. When the money lines predict a tie, the prediction is counted as incorrect. The scrip odds_analysis_year_ml.py produces this analysis.

| Season | Number of Games | Percentage Predicted Correct |

|---|---|---|

| 2007-08 | 1230 | 68.86% |

| 2008-09 | 1230 | 69.84% |

| 2009-10 | 1230 | 70.24% |

| 2010-11 | 1230 | 68.29% |

| 2011-12 | 990 | 68.38% |

| 2012-13 | 1229 | 68.43% |

| 2013-14 | 1230 | 68.46% |

| 2014-15 | 1230 | 70.08% |

| 2015-16 | 1230 | 69.02% |

| 2016-17 | 1230 | 65.85% |

| 2017-18 | 1230 | 67.97% |

| 2018-19 | 1230 | 66.42% |

| 2019-20 | 692 | 67.20% |

| Total | 15211 | 68.43% |

A couple notes about these numbers. There were less games during the 2011-12 season because of a labor dispute between the NBA players and team owners resulting in a lockout shortened season. The 2012-13 data is missing a game because that game did not have complete betting odds. The 2019-20 season ended prematurely because of coronavirus resulting in fewer games that season.

Another note is that the percentage of games predicted correct by the betting odds seems to go slightly down with time. This could just be randomness, since it is not a significant decrease. It also could be explained by the prevalence of three point shooting going up during this time period. Higher amounts of three point shots creates more game to game variance of scores. In the future, I would like to explore the precise relationship between three point shooting and Vegas’ ability to correctly predict winners.

Betting Strategies

Three main betting frameworks are used: always bet the favorite, bet \$100 on every game using a machine learning model, and bet \$100 every day there is a basketball game using a machine learning model. Within each of these frameworks, multiple strategies are used.

The purpose of the always bet the favorite framework is to show that in order to win money betting one cannot just always bet the favorite. Even if you win a large percentage of your bets, if you always bet the favorite, you will lose money in the long run. This is mathematically explained by the betting margin that appears in equation $(2)$.

To contrast the always bet the favorite framework, in the other two frameworks a “constant of decorrelation”, $C$, $0.0\leq C\leq 0.3$, is used. This constant is partially inspired by the constant, $c$ used by Hubáček, Šourek, and Železný in their novel loss function. The constant $C$ produces the following betting strategy: the bettor bets on a game if and only if

\[\begin{equation}|\hat{p}_m - \hat{p}_o| \geq C,\end{equation}\]where $\hat{p}_m$ is the model’s predicted probability of the home team winning, and $\hat{p}_o$ is the betting odds’ predicted probability of the home team winning. With this strategy, the bettor only bets on games where the model’s predictions differ from the betting odds predictions by $C$. This is theoretically a simple way to combat the issue of losing money when always betting the favorite. It is only successful if the predictive model is effective at predicting the winner of games when it disagrees with the betting odds.

For each of the frameworks, this betting strategy for various $C$’s is simulated on the 2018-19 season data. The machine learning models used are logistic regression and a multilayer perceptron model, which are trained on the seasons 2007-08 through 2017-18. See Predicting NBA Games with Machine Learning for more specifics on the models.

It is worth noting for the two models, their correlation coefficient with the betting odds predictions on their predictions for the 2018-19 season. The logistic regression model has a correlation coefficient of 0.88, and the multilayer perceptron model has a correlation coefficient of 0.85.

The following sections contain the results of the betting simulations.

Always Bet the Favorite

For each simulation of always betting the favorite, a favorite probability $f$, $0.55\leq f\leq 0.75$, is fixed. In the simulation for a fixed $f$, the bettor bets $100$ on every game where the betting odds predicted probability of the favorite winning is greater than or equal to $f$.

The following table has the results. The code that produces these results is time_betting_analysis.py.

| Favorite Prob | Money Lost | Number of Bets | Percentage Won Bets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.55 | $31396.37 | 937 | 49.73% |

| 0.60 | $23627.21 | 791 | 53.98% |

| 0.65 | $16552.28 | 621 | 58.78% |

| 0.70 | $12783.68 | 509 | 61.89% |

| 0.75 | $9003.68 | 391 | 65.73% |

Bet $100 Every Game

In this framework, we fix a constant of decorrelation , $C$, and bet \$100 on every game that satisfies $(6)$ for the given model. The constants used are 0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, and 0.3. The result of the models are in the following tables. The code that produces these results is naive_betting.py.

Logistic Regression Bet $100 Every Game

| $C$ | Money Lost | Number of Bets | Percentage Won Bets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | $39011.07 | 1059 | 45.14% |

| 0.05 | $24340.32 | 638 | 41.38% |

| 0.1 | $16281.16 | 380 | 36.58% |

| 0.15 | $8556.54 | 182 | 31.32% |

| 0.2 | $4031.26 | 72 | 23.61% |

| 0.25 | $2300.43 | 33 | 15.15% |

| 0.3 | $1239.39 | 14 | 7.14% |

Multilayer Perceptron Bet $100 Every Game

| $C$ | Money Lost | Number of Bets | Percentage Won Bets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | $35497.43 | 1059 | 46.93% |

| 0.05 | $25343.64 | 716 | 44.97% |

| 0.1 | $12940.26 | 379 | 43.01% |

| 0.15 | $7779.83 | 182 | 32.42% |

| 0.2 | $3127.61 | 77 | 29.87% |

| 0.25 | $929.0 | 29 | 27.59% |

| 0.3 | $555.0 | 18 | 27.78% |

Bet $100 Every Day

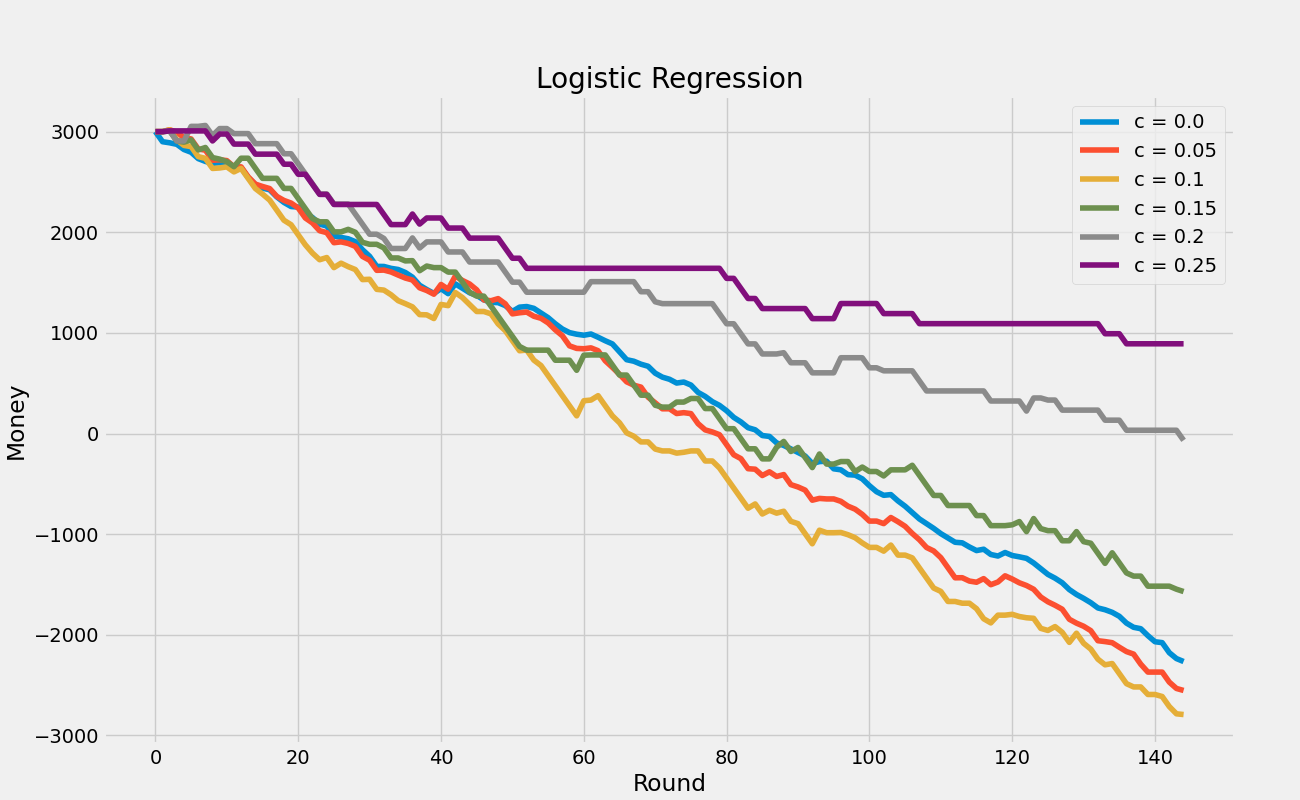

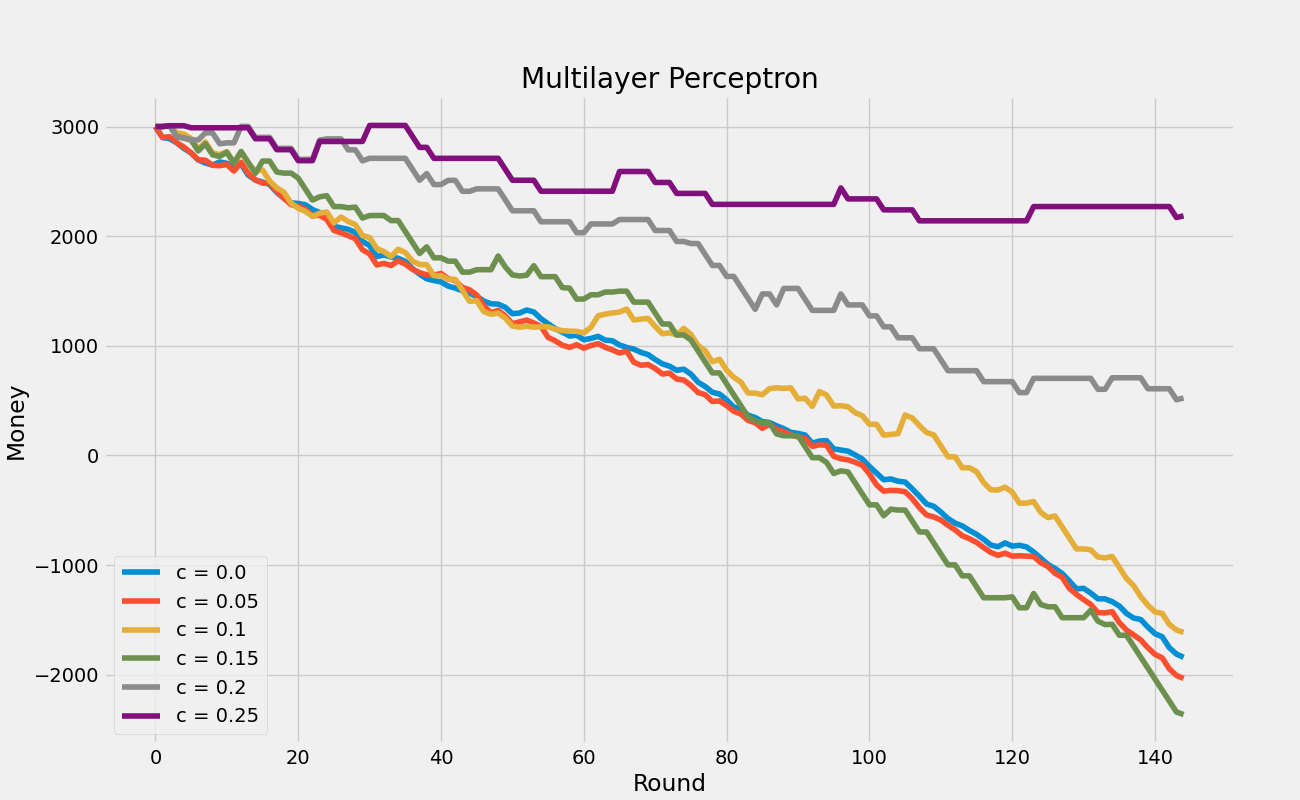

In this framework, for each simulation, a constant of decorrelation, $C$, is fixed. This is the framework where rounds of games are used. Each day when a basketball game occurs in the 2018-19 season is considered a round of games. For each day, the games that satisfy $(6)$ for the fixed constant $C$ are bet on. For each day when there is a game satisfying $(6)$, \$100 dollars is bet, and the \$100 is divided evenly amongst the games satisfying $(6)$.

For these simulations, the amount of money as rounds go by is graphed for each $C$. The bettor is assume to begin the season with \$3,000. The script that does this analysis is time_betting_analysis.py.

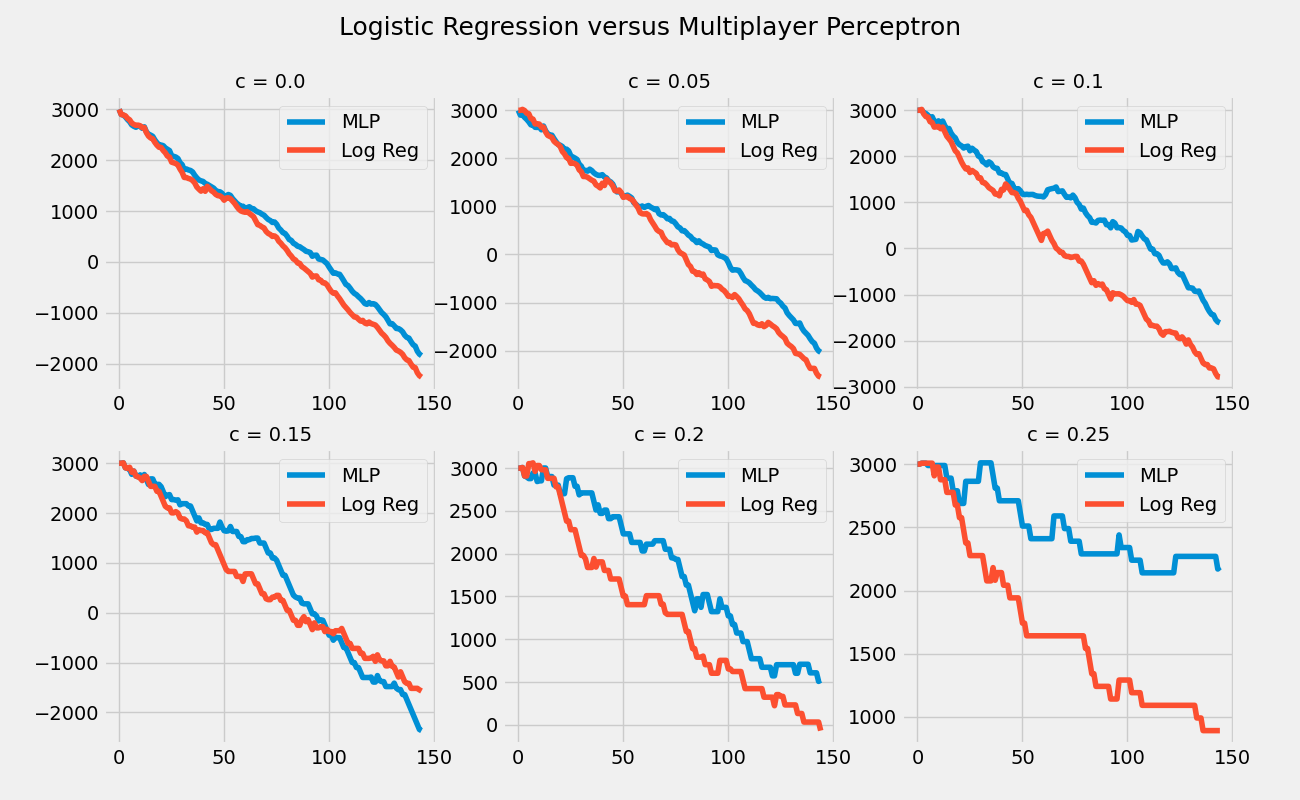

To compare the two prediction methods, the following graphs for each $C$ graph the multilayer perceptron (MLP) versus the logistic regression (Log Reg) results of the simulations. As in the graphs above, the x-axis is the round and the y-axis is the amount of money the bettor has.

Conclusions and Future Work

In every simulation, a significant amount of money is lost. The use of the constant of decorrelation $C$ does not work because the models predictions are actually worse the more they differ with the betting odds predictions. This is seen from the tables in the Bet $100 Every Day Section, where the percentage of games predicted correctly goes down as the constant $C$ goes up. It is worth noting that those tables also show that the multilayer perceptron model does significantly better than the logistic regression model. In the graphs of the multilayer perceptron model versus the logistic regression model, the multilayer perceptron also does better, ending with more money in every case except when $C = 0.15.$

For future work, I hope to improve these models in three ways. One is to introduce more advanced statistics to make the prediction models more robust. The statistics used for these models are only basic box score statistics. The second is to try using a loss function like the one in [HSZ]. The third is to try using a more sophisticated strategy in placing the bets, perhaps also mimicking the strategy in [HSZ].

Reference

[HSZ] O. Hubáček, G Šourek, F. Železný, Exploiting sports-betting market using machine learning, International Journal of Forecasting, 35 (2019), 783-796.